Halloween is approaching. Everyone is getting out their costumes, setting up the

spooky decorations and watching classic horror movies. It’s also the time some gamers take to play

their favorite scary games, as well as October-themed specials going on for

games like Killing Floor and Team Fortress 2.

But for a lot of us, the scares are what we’re looking

for. Now’s the time to play the classics

like Eternal Darkness, Resident Evil, Silent Hill 2, System Shock 2 or Amnesia.

This year I have a recommendation on another horror

game. I’ve already gone over how Clock Tower is the scariest game ever made, but this

year I’m taking a moment to appreciate the aspects of a classic horror game

that don’t contribute to the horror.

I’ve always held a soft spot for 90s adventure games. I was quite a fan of King’s Quest 5 back in

the day, and even now with all the advancements companies like Telltale Games

have made to the genre, I can still play some of the adventure games from the

days of lesser graphics and game design.

I still love The Curse of Monkey Island, the Phantasmagoria games, and

The Neverhood as much as I ever have.

Sure they had annoying puzzles and huge leaps in logic when it came to

progressing through them, but the stories were so well told and presented, I

couldn’t help forgiving them.

That’s why when the opportunity came knocking, I bought the PC game adaptation of the short story I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream by Harlan Ellison. I had heard about the game being scary,

unsettling and overall pretty good, so when it was on sale for Halloween on

Steam earlier last year, I gave it a try myself.

Naturally, I enjoyed the traits many of the best 90s

adventure games sported: detailed artwork, a good story, and (mostly) good

voice acting to boot. Unlike some of the

other 90s adventure games though, I was also impressed with IHNMAIMS’s overall

design as a game because it managed to largely avoid the pitfalls many

other adventure games of the time are infamous for.

As I stated, many adventure games in the 90s had design quirks,

for lack of a better term. Anyone who

has played them knows the complaints as well as the jokes made about them: an increasing

load of inventory items, illogical solutions with only one way to do them you

likely had to find out through guesswork and not to mention some (usually from

Sierra) that killed you or rendered the game unwinnable without fair warning.

IHNMAIMS averts the overstocked inventory problem right off

the bat through its premise. The story

is about the last 5 humans on earth being tortured by a human-hating godlike

supercomputer named AM (Allied Mastercomputer), voiced by Ellison himself. AM makes each human play a game of his own

making, each one preying on their weaknesses.

That means every character, along with their scenario, has their own

inventory and map.

Each scenario’s landscape is relatively small (about half

the size of a suburban elementary school), making them easy to navigate and greatly

reducing backtracking. It’s much like Telltale

Games’ episodic adventure games released today in how it takes the story one

chapter at a time. Not only does this

mean you don’t have to go to hell and back if you forgot something, but because

there’s less to cover, should you decide to take the desperate practice of

trying to use everything you have on everything else to get something to happen,

it’s a lot quicker.

But in my playthrough of the game, that didn’t happen. With the exception of a few points of

guesswork and vagueness, IHNMAIMS is relatively logical in its solutions, and

when the rules of logic are bent in

AM’s twisted game, clues are given.

Without spoiling the solution, I cite a point in Ellen’s

scenario. In it, she must grab a chalice

from a room being guarded by a vicious sphinx that scares her away when she

comes in. However, if the player looks at

the room through a security monitor in another room, it doesn’t show the

sphinx. Hmmmmmm…

|

| She doesn't even touch the thing! |

That, however, should not happen, and the game won’t kill

you for one slip-up. While it is possible to die, there are very few instances

it can happen, giving the game the relaxed play of Monkey Island, but with some

of the sense of peril of King’s Quest, where everything is trying to kill

you. In any situation in which you can

die, you can see it coming and it’s avoidable.

For example, in Ted’s scenario, he can hear the sounds of

wolves getting closer every time he enters the central room of the castle, and

the front door is missing a hinge. It

gives you several chances to figure out a way to shut the door, so if they bust

in and you die, it’s your own fault.

Other times the game doesn’t need to warn you and has you

rely on your common sense. If you cut

the airbags in a blimp in order to lower it to the height it needs to be at,

common sense tells you that you shouldn’t cut any more than that, or else…

In the same scenario, the designers anticipated a player’s

thought process in a specific way.

Instead of cutting the air bags, you can instead try to shoot a hole in

it with what is described as a bulky, single-shot handgun. However, you’re supposed to realize that the

reason it’s bulky and has one shot is because it’s a flare gun.

Fire does not go well with blimps.

Instead of simply giving a generic “I can’t use these two things together” line, the game knows what you were thinking, and you thought

wrong.

In one last brilliant design decision, each scenario has

multiple endings that give the game flexibility. These endings are determined by the

character’s moral actions through their chapter, long before games like

Infamous and Mass Effect implemented their own morality measurements. For example, having Ted be unfaithful lowers

his morality, and having Nimdok use ether to ease the pain of someone suffering

raises his.

There are different ways for the successful endings to play

out as well; there isn’t only one proper set of solutions. Although the alternate solutions never diverge

far from what you’re supposed to do, they allow for some tangential thinking.

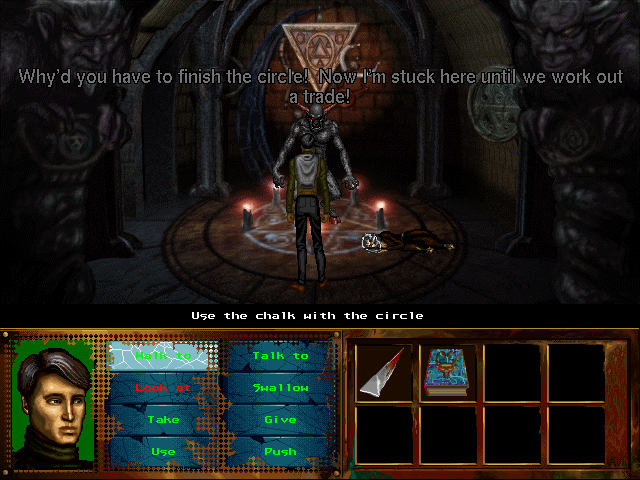

For example, in Ted’s scenario, you’re told that there’s a

clue on the servant woman’s tapestry in her room. There are two ways in: you can either sleep

with her (lowering morality) or give the demon you summon that can open locks a

bit of energy to have him open the simple lock on her door. Alternate solutions like that also help give

the game some incentive to play through it again.

Unfortunately, much of the good about the game I just went

over sort of falls apart at the game’s finale, where the puzzles are abstract,

you’ll almost certainly need a guide, and you die permanently, but the 80% of

the game getting to that point is still a treat.

Before playing it, I thought I Have No Mouth and I Must

Scream was a cult classic because of its well-told story, like most

fondly-remembered adventure games, but having played it myself, I see there’s

more to it than that. While it shows its

age in some areas, IHNMAIMS holds up pretty well, even by today’s

standards. If you’re looking for a

creepy game to play this Halloween, or just a good adventure game in general, it’s a solid buy.

No comments:

Post a Comment