Immersion. When I

think of the word “immersion”, I see myself being lost in a game’s world. I focus on the screen and ignore everything

else, unaware of how much time is passing in the real world. I become the character and never truly stop

playing even after I’ve pressed the pause button. I’ve known about what immersion is for a while, but something

happened that made me realize just how effective it is as a tool; a tool not

just for having fun with a game, but discovering more about ourselves.

The game was Mass Effect.

One of the first 360 games I ever decided to give a try, and it was incredible. It had action, drama, a rich universe, and a

villain voiced by the same actor who gave Kakuzu his excellently villainous voice in Naruto.

That presentation was backed up by flowing gameplay that

never stopped, even during exposition.

Mass Effect constantly kept me involved with its dialogue choices and

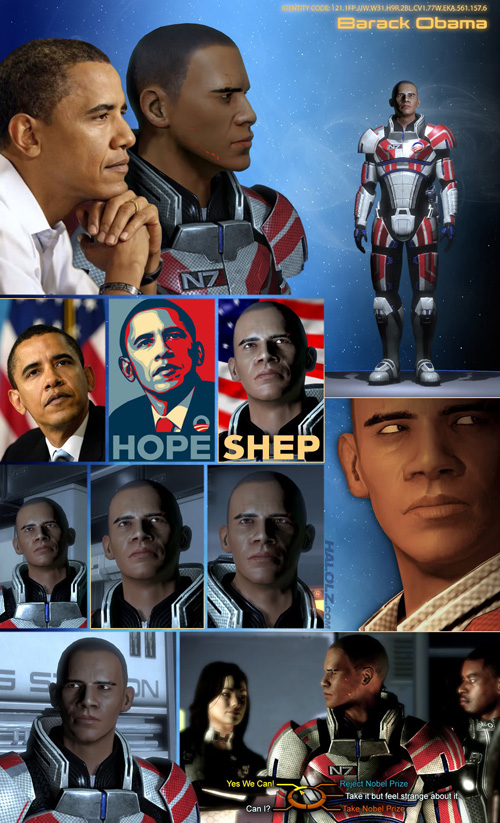

moral choice system, making me really feel like my hero onscreen (helped by the

character being customized to look a lot like me).

|

| You know how it is... |

In my first playthrough I did what came naturally, making

choices I would make in the situations given, like any normal gamer would

do. Overall I was practically a saint,

always taking peaceful solutions and racking up paragon points. I only got a few renegade points for relatively

harmless acts and misinterpretations on the part of either me or the game.

After beating the game, I felt I didn’t do enough sidequests,

so I made a new game to explore outside of the main story more. However, I already played as myself, so I decided

to role play as someone else entirely for different results.

Thus began the adventures of commander Jerk Shepard: Asshole

Extraordinaire. Jerk killed people when

he could, punched reporters, insulted his crew, cut off the council, and always

chose the aggressive option when available.

It was funny for a while, sadistically laughing at people’s reactions to

Jerk being one of the most unlikable bastards in the galaxy (and when you’re a

Specter, they can’t do a thing about it).

But then one particular incident happened, and I did not laugh at all.

Conrad Verner. Most

people who have played Mass Effect likely already know where I’m going with

this, but for those who haven’t, Conrad is basically Commander Shepard’s

fanboy, and greatly idolizes him. Conrad told Jerk that he thought he could be a Specter too, since Jerk was the first

human specter and gave him hope.

If this were my original playthrough, I would’ve sternly,

but calmly told him of the dangers that comes with being a specter, patted him

on the shoulder, told him to train, and maybe would’ve signed an autograph (had

any such options been given).

Jerk Sheppard had a different way of telling him how hard

being a Specter is. Jerk aimed a gun at

Conrad’s face, saying “This is what it feels like having a gun to your

head! I go through this every day!” He went on to say that Conrad didn’t have

what it took and, after Conrad started whimpering, also said that the guy was pathetic.

After that debacle, Conrad practically cried, saying that he

thought Jerk was a hero, and that heroes aren’t supposed to act that way, before

running away.

It is at that point I stopped, controller still in hand, and

thought. “Wow… I’m an &^$%#*#.” It was a genuine emotional response.

Mass Effect was so immersive, and the graphics and voice

acting were so convincing, for a brief moment, I couldn’t help but feel like what I had done wasn’t

just in a game. I really felt like I had

just ruined someone’s hopes and dreams.

Like I had ruined myself as that man’s role model, and made him feel

like dirt at the same time. I saw a bit

of myself in Conrad. I can’t imagine how

crushed I would be if one of my heroes threatened or insulted me.

A similar feeling happened later in the game. Emily Wong, a journalist character who is not so

well-liked, asked Jerk to plant a bug for her to do a

story on poor working conditions. Had this been my initial playthrough, I’m

not sure what I would have done.

On one hand, being a journalism major, it’s in my nature to

help other journalists, and a story like that could do some good. On the other hand, her methods may have been shady. I don’t know how much the law has changed in

the future of Mass Effect, but when I come from, bugging is an invasion of

privacy.

But what did Jerk decide on?

He said he’d do it, then went back and lied by saying he placed the bug. When Wong said she didn’t get a signal, Jerk

insisted that they must have found it, but still accepted payment for placing it. Then Wong, depressed, went back to talk to

her editor about another story subject.

Ignoring that Jerk never went ANYWHERE outside of Wong’s

sight before saying he planted it, that was a dick move on many levels.

Firstly, lying is wrong, especially in this case. It’s an

excuse to get out of Jerk’s own laziness.

Secondly, he accepted payment for nothing.

That is stealing! Lastly, that poor journalist is going to be

pressed for a story now. I know what

it’s like for a story I’m looking forward to or was working on to be shot down

because of a lack of cooperation. Like

Conrad, I saw a bit of myself in the way Emily Wong walked away from Jerk. That was Mass Effects way of saying “You are

no less evil than Saren!” Sure, Jerk had punched her earlier, but in that case, the audacity of it was actually pretty funny. In this case, it was more relatable.

Therein lies the brilliance of Mass Effect. It is so immersive, it makes it difficult to lie to yourself. “To thine

own self be true.” As much as you try to

repress choosing the choices you would ordinarily, you won’t be able to escape its

full emotional potential. Even before

the Conrad scene, I hesitated to choose some of the options before reminding myself

“wait… I’m Jerk Shepard.” I had to

consciously play against who I really am, which tells me that I’m a good person

at heart. That is immersion, and one of

the big reasons Mass Effect is one of my favorite games of the

generation.

The aforementioned Conrad scene is at the 4:50 mark.

No comments:

Post a Comment